July 26, 2019

At the intersection: Recognizing challenges faced by our justice-involved community members living with HIV

Both HIV and mass incarceration have been burning issues in the American public for decades. America’s long history of tough-on-crime tactics and fearmongering against people living with HIV and AIDS has created a permanent disparity in the ways we engage with both groups. But what many people fail to see are the many ways these two groups often intersect. In the Getting to Zero Illinois (GTZ-IL) plan, however, this particular intersection is outlined in hopes of uplifting and reaching out to those affected to provide the extra-attentive care that they need.

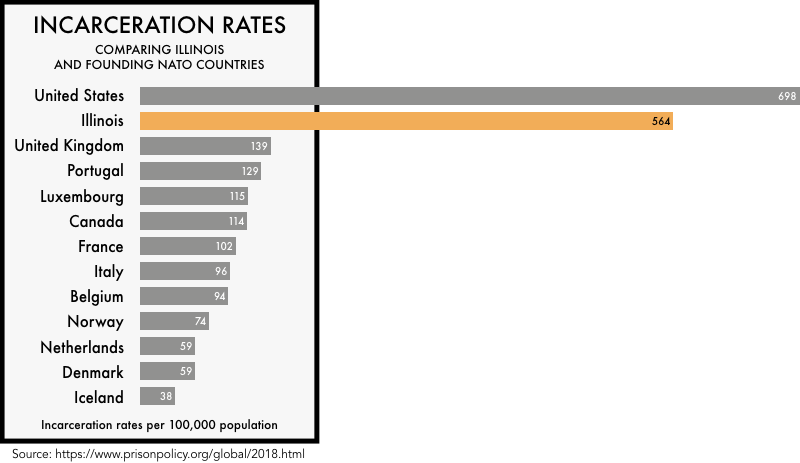

In the U.S., we incarcerate more of our population than any other developed nation, around 716 people per 100,000. Not only that, but who we incarcerate is extremely imbalanced. According to a 2017 Prisoner Report by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the imprisonment rate for Black women is almost double compared to their white counterparts. The same report showed the divide was even worse for Black men, with imprisonment rates being around 6 times higher than white men. Other marginalized groups, such as members of the LGBTQ community, suffer from similarly unfair targeting by the criminal justice system. In an article released by the Williams Institute, they include that members of the LGB community make up about 3.5% of the U.S. population, but 5.5% of incarcerated men are gay or bisexual and 33.3% of incarcerated women are lesbian or bisexual. Even more, people of transgender experience are very susceptible to violence and mistreatment within the prison system, as they are 10 times more likely to be assaulted by other inmates and five times more likely by prison staff. These vulnerable communities are often under attack by the police and justice system, and many are also disproportionately impacted by HIV.

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, in 2015 there were around 17,150 people in federal and state prisons with HIV. The communities most affected by HIV and AIDS are frequently already vulnerable due to other forms of systemic oppression and it is because of this oppression that the formerly incarcerated, especially those living with HIV, must be treated with the utmost care. HIV/AIDS has always been surrounded by stigmas relating to racial, sexual and gender minorities. Likewise, those who have previously been arrested or incarcerated face societal judgement, even if the crime was non-violent or committed as a juvenile. Because of this, people who were formerly incarcerated struggle to find jobs or proper housing. Even public housing options can be unobtainable due to state regulations banning those with felonies from even stepping foot on the property. These problems are only exacerbated if the person is also living with HIV. Despite antiviral medication being available in a prison or jail setting, once released, justice-involved people often have inconsistent access to life-saving medications and other important resources.

With all these factors in mind, it is important that GTZ-IL does not ignore these groups who require the most consideration. The goal of GTZ-IL is to advocate and provide services for those who live with and are vulnerable to HIV, but those who are justice-involved may be hesitant to get involved due to a history of mistreatment from different institutions. It is with this understanding of the history of systematic persecution that we must refocus and increase efforts to care. For instance, GTZ-IL Strategy 53 indicates we will maintain and expand resources for programs that provide HIV/HCV screening and linkage, medical care, behavioral health care, and supportive services for people who are justice involved, including those living in jails and prisons and those recently released from these facilities.

We must also ensure that we support already existing programs and organizations doing good work to help these communities. Two GTZ-IL partner organizations in particular, the Chicago Women’s AIDS Project (CWAP) and the AIDS Foundation of Chicago (AFC), do amazing work leading initiatives that serve justice-involved individuals. CWAP runs a program called Returning Sisters that caters specifically to women living with HIV who have a history of encounters with the justice system, while AFC coordinates the Safe and Sound Return Partnership (SSRP) which works to reduce barriers to housing, employment and other important utilities for justice-involved individuals by linking them to case management and supportive services. By ensuring funding to these programs and others like them, we can hope that stigma around both the formerly incarcerated and those living with HIV can be reduced, and they can receive the support they need to integrate back into society and live healthy, fulfilling lives.